Broader Patterns: Suicide and Addiction in 19th Century Swansea

Fanny’s tragedy is far from isolated. The streets surrounding Matthew Street and the area now known as Greenhill bore witness to repeated incidents of suicide and mental breakdown, often compounded by addiction and social hardship.

The Case of Thomas Ridd (1880)

A 45-year-old baker from Matthew Street, Thomas Ridd returned to Swansea from Australia and fell into depressive isolation. After a series of financial troubles, including the collapse of the West of England Bank, Ridd died by suicide using a revolver. His inquest pointed to “temporary insanity” brought on by psychological distress and economic insecurity (The Cambrian, 16 Jan. 1880).

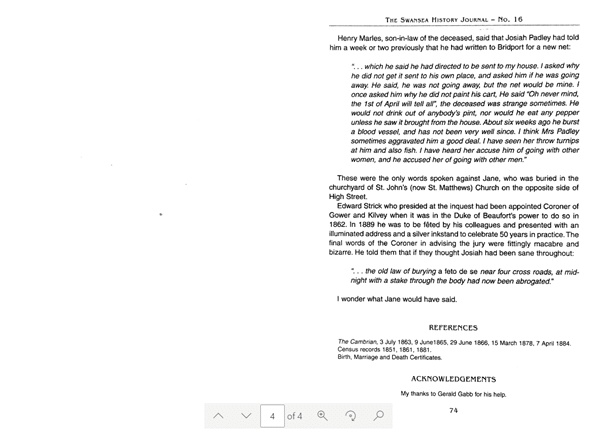

A SWANSEA SUICIDE— The inquest on the body of Thomas Ridd, 45, baker, who committed suicide in Matthew street, Swansea, about midnight on Thursday reported in our impression of last week, was held at the Black Horse Inn, Dyvatty-street, on Saturday morning, before Mr. Edward Strick, the borough coroner. The first witness examined was Ann Treharne Widow, who stated that she was a sister of the deceased and lived in Matthew street. Deceased had resided with her ever since he returned from Australia nine or ten years ago. He went to Australia in the year 1854 with his brother for the benefit of his health. He brought home a considerable amount of money, and built some houses in Baptist Well street. He was a joiner before he left England. He had been a baker with his brother about five years, but left the bakehouse about four or five months ago. Since then he had complained very much of weakness in the chest, and was very nervous. He also complained of his head. Had never seen him the worse for liquor, but he used to take a few pints of beer in the course of his day’s work. He was very low-spirited at times. He had no occupation after leaving the bakery, and spent most of the time in the house. He had never said anything which would lead witness to suppose he was tired of his life. When the West of England Bank failed he bad some money in it, and some in the Glamorganshire Bank. He had got the money out and kept it in the house, and asked witness for a revolver which belonged to her late husband, in order to protect himself. He was very timid, and the bank failure affected him very much. During the past week he was more depressed than usual, and very silent. On Thursday night he went upstairs, and witness heard him draw from under the bed a box in which he kept his money. A few minutes after she heard a shot fired. She went upstairs and saw the deceased with a revolver in his hand. He was standing up. He pointed the revolver at her, and said, “Stand off from me.” He then fired again. Witness went downstairs. She was frightened. She sent for her brother, and he came, and Dr. Rees was fetched. Deceased had a letter from Hamburg in November which appeared to trouble him very much. Witness did not know its contents, but it was something about a lottery.—Mr. A. B. Rees, surgeon, said he saw deceased about eight o’clock on Sunday evening, when he seemed quite rational. Had seen him frequently during the last 18 months, and never noticed anything strange about him. About half-past twelve on Thursday night witness was informed that deceased had shot himself. Went to the house, and found him lying on the floor of the bedroom. Found a very small wound behind the right ear. Told the brother that the wound was fatal. He was becoming insensible. Police-constable Gill said that about quarter past one on Friday morning he was informed by Dr. Rees that deceased bad shot himself. Dr. Rees also handed him a six-chambered revolver, three barrels of which had recently been discharged. Went to the house, and saw deceased. Assisted to undress him, and lay him on the bed. Saw Dr. Rees find a bullet on the bed, under a hole in the ceiling. Took another bullet out of the ceiling. Searched deceased, and found on him about £80 in money and a Swansea bank deposit note for £163 16s. 10d.— John Ridd, grocer and baker, 108, High-street, said deceased was his brother. He bad searched his box, and found several tickets and papers relating to the Hamburg State lottery. Deceased was very reserved. They had agreed to leave the country together in a short time and go to California or Africa for three or four years. He brought about £850 from Australia.—The Jury returned a verdict of Suicide whilst in a state of temporary insanity.

William Williams (1901)

A foreman mason, Williams hanged himself in a hayloft near the Grammar School, leaving behind a widow and seven children. No immediate cause was identified, though his depression was noted by co-workers. Again, the coroner’s jury returned a verdict of temporary insanity (The Cambrian, 17 May 1901).

William Lewis (1901)

A labourer from Matthew Street, Lewis survived an attempted suicide while under the influence of alcohol. Court reports describe how alcohol exacerbated his despair, leading to the attempt. He was later released on condition of good behaviour, pointing to the limited mental health interventions available at the time (The Cambrian, 24 May 1901).

These stories reflect a consistent pattern: economic hardship, untreated mental illness, and substance misuse contributing to tragic outcomes. The lack of professional mental health services in 19th-century Swansea meant that personal crises often culminated in death, shame, or incarceration.

Contemporary Reflection and Relevance

Today, suicide remains a leading cause of death among young people in the UK. According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), in 2022, the suicide rate for males was 17.2 deaths per 100,000—more than three times higher than for females. Wales consistently records some of the highest suicide rates in the UK. Substance misuse, social isolation, and economic vulnerability continue to be major contributing factors.

While our understanding of mental health has improved, stigma remains. The historical silence around figures like Fanny Imlay reminds us how easily vulnerable people can be overlooked or erased. Her story—quietly interwoven into Swansea’s past—calls us to listen more attentively to those on the margins.

Matthew’s House and similar organisations now exist to do just that. By offering food, conversation, dignity packs, and non-judgemental space, they help rewrite stories of despair into narratives of hope. Public history projects like this trail bring those invisible struggles into the light.

Domestic Violence in the Area

Domestic violence was a painful reality for many families around Greenhill and the streets surrounding what is now Matthew’s House. These streets — Tontine Street, Jockey Street, Powell Street, and Matthew Street — bore witness to harrowing episodes of abuse, often exacerbated by poverty, addiction, and lack of support. The stories that survive today, recorded in court reports from local newspapers, are sobering insights into the lived experiences of women and children during the 19th century.

While such cases rarely reached the police courts at the time, those that did were often of extreme severity. Many incidents went unreported, dismissed as private family matters. Still, in some moments, justice — or at least intervention — was served. These are a few documented cases from the area:

- William Rees (1876, Jockey Street)

Found beating his wife while drunk, he had been previously convicted multiple times. He was sent to prison for seven days without the option of a fine.

➤ The Cambrian, 2 Feb. 1876

William Rees was charged with a similar offence. P.C. 22 said that on Sunday morning, about seven o’clock, he was on duty in High-street, when he heard screams coming from the direction of Jockey-street. On going there he saw the defendant’s wife run out of the house with a child in her arms. She said her husband had been beating her. He tried to make peace between them, but the defendant became very riotous, said he could use his fists as well as the constable, and threatened to do so. The defendant denied being drunk, but was convicted, and having been three times previously convicted, was sent to prison, without the option of a fine, for seven days.

- John Hoare (1878, Tontine Street)

Found brutally assaulting his wife and daughter, he was imprisoned for six months and granted a judicial separation under new legislation, protecting his wife from further abuse.

➤ The Cambrian, 12 July 1878

JUDICIAL SEPARATION OF MAN AND WIFE BY THE MAGISTRATES.—REVOLTINGLY CRUEL CONDUCT. — John Hoare, hobbler, was charged with being drunk and riotous and assaulting his wife. P.S. Williams (2) deposed that on Sunday night he saw the prisoner beating his wife in Tontine-street. The wife and daughter’s faces were covered with blood. Prisoner said he had struck his daughter by mistake. There was in the crowd an alarm that prisoner had stabbed his daughter, but no knife was seen. P.C. Bowman, who was there before the sergeant, said he heard cries of murder, and saw the prisoner holding his wife with his left hand, and striking her on the head and breast with his right hand. Witness had to “choke prisoner off” before he would let go his hold. The little girl was bleeding. This was in the house. Prisoner again struck his wife in the passage. Prisoner “Anne, tell the truth. Did I strike you outside the door?” The wife did not answer, and the police said they bad some difficulty to get her to the court, because she did not wish to prosecute. On being sworn, the wife said the row commenced about 20 minutes before the police came. The marks on her face were inflicted by the prisoner’s hands, She had done nothing to provoke him; the quarrel took place because she had no money to give him. She had four children and would not live with him if she could get a separate maintenance. He was half drunk when this took place. She was now afraid to live with him. He had attempted to gouge her eye out. The prisoner said he had only been out of gaol a fortnight. He had been there because he could not find sureties to keep the peace towards his wife. The Stipendiary, after consulting awhile with his colleagues, said prisoner was convicted of an aggravated assault upon his wife. The evidence showed that he had beat her both inside and outside the house in a cruel and cowardly manner and there was strong reason to believe that during one part of this attack he attempted to injure her severely. Her eye bore the strongest mark of an attempt to gouge it out. It appeared that he had been in the habit of beating her for some time past; that she had been afraid to live with him, and that she had applied to this Court to have prisoner bound over to keep the peace. She had given evidence against the prisoner again and again. and he had been sentenced to imprisonment, as he himself had admitted just now, when he said “he wondered she was not ashamed to put him in prison so often;” as if he thought the poor wretched woman ought to stop at home to put up with any amount of cruel blows, when the husband may think fit to amuse himself by kicking her. This was a very sad case, and no one could do otherwise than feel the deepest sympathy for the poor woman who was placed in the power of a man so cruel and cowardly as the prisoner. He (the Stipendiary) could not conceive of a more wretched and unhappy life than such a woman must lead. No doubt it arose chiefly from the prisoner’s indulgence in drink and his keeping his family on short commons. The Bench did not think they would be doing their duty in such a case as this (where the prisoner had been upon various charges convicted more than 20 times before the Court and several times for serious assaults upon his wife) if they did not go the full extent of their powers. He would now be imprisoned and kept to hard labour for six calendar months, and, not only that, but the Bench would put in force an Act of Parliament which had been passed in the present year, by which it is enacted that if a husband is convicted of an aggravated assault, as prisoner now was, and if the Court is satisfied that the future safety of the wife is endangered, the Court may order that the wife shall no longer be bound to cohabit with her husband and such order shall have the force of a judicial separation. The Court may also order that the husband shall pay such weekly sum as they may consider to be in accordance with his means and the means the wife may have for her support, and this order may be enforced by process of law. Now he (the Stipendiary) thought that if the Bench sat here to the end of the present century, they could never have to deal with a case to which this new law would be more clearly applicable than the present one. Here was a woman who had been living a life of horror and misery, who declared that she was afraid of her life, and no woman could be otherwise under such circumstances. Therefore the Bench would make the order that the wife should no longer cohabit with the prisoner, and that he should, when he came out of prison, pay her the sum of 5s. per week. She would therefore be quite independent of the prisoner in the future, and the Bench hoped that she would never again be sleeping under the same roof as prisoner. He was then removed, muttering that he was as glad to be rid of her as she of him.

- Richard Walters (1881, Tontine Street)

After blinding his wife in one eye with a brick and leaving her severely bruised, Walters was sentenced to six months’ hard labour and bound to keep the peace for a further year.

➤ The Cambrian, 5 Aug. 1881

ILL-TREATING HIS WIFE. -Richard Walters, of Tontine- street, remanded from Tuesday, for assaulting his wife, was again brought up this day. The wife was in a deplorable state, her eye having been nearly knocked out by a brick, on the 31st of July. She was also covered with severe bruises on the arm and other parts of the body, showing that she had been very brutally treated. The defendant was an old offender, having before been convicted of assaulting his wife, who had what is called, “A Court separation” granted him. The Stipendiary said that he never saw greater injuries inflicted on a woman. It was a most brutal and cowardly assault, and as he had done the same thing before, he committed him for six months and after that to find sureties keep the peace for 12 months.

- Thomas Evans (1884, Tontine Street)

Evans neglected his common-law wife, who became reliant on parish relief. He was imprisoned for one month.

➤ The Cambrian, 7 Mar. 1884

NEGLECTING TO MAINTAIN A WIFE.—Thomas Evans, chairmaker, Tontine-street, was summoned for neglecting to maintain his wife, who is chargeable to the common fund of the Union. The defendant said that he had lived with her for 28 years, but he was not married to her.—The Bench said if he lived with the woman for so many years, and spoke to and of her as his wife, he must take the consequences. He was sent to prison for one calendar month.

- Edward Matthews (1893, Matthew Street)

Convicted of assaulting his wife while intoxicated, he was fined 20 shillings. The testimony revealed a household plagued by violence and financial instability.

➤ The Cambrian, 14 July 1893

A LIVELY SHOP.—Edward Matthews, labourer, 18, Matthew-street, was summoned for assaulting his wife, Elizabeth Matthews, on the 6th inst.—Complainant stated that her husband struck her several times, blackening her eye, whilst she was in bed. He was under the influence of drink at the time.—For the defence, Matthews stated that his wife was continually annoying him. On one occasion she stabbed him with a fork, and she often threw the plates and dishes at him. Complainant retaliated by stating that her husband wouldn’t work, and if it were not for her mother, she (complainant) would be starved. The Bench thought the case proved, and imposed a fine of 20s. inclusive.

What Can We Learn?

These accounts, while deeply disturbing, shine a light on the lived trauma many endured and the resilience of women who often had little support. They remind us that domestic abuse is not a modern issue — it has long haunted communities, hidden behind closed doors. Sharing these stories is not about sensationalism but about remembering those who suffered in silence and recognising how far — and how much further — we still need to go.

Modern Reflections

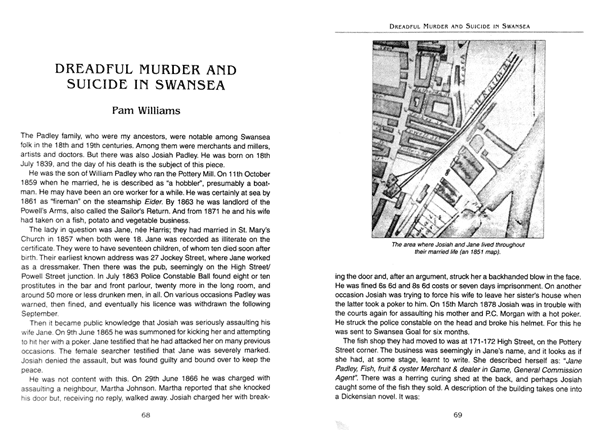

Today, the streets once known for violence and hardship are being reclaimed as places of dignity, safety, and hope. Matthew’s House offers support without judgment, providing sanctuary, advocacy, and friendship for those affected by trauma. The transformation of St. Matthew’s Graveyard into Greenhill Gardens is a symbol of this change — a space once marked by loss now blooming with life.