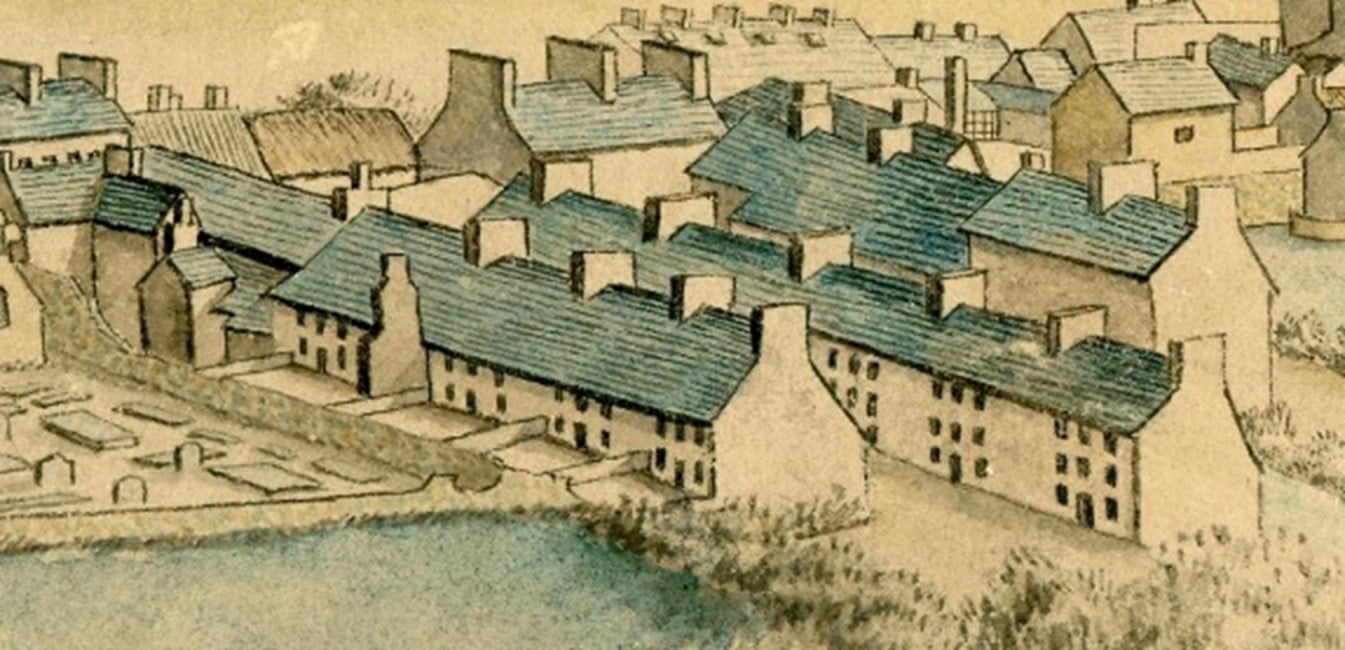

Sanitation, Overcrowding, and Health Crises

Two pivotal surveys shed light on the appalling housing conditions in mid-19th-century Greenhill and nearby areas:

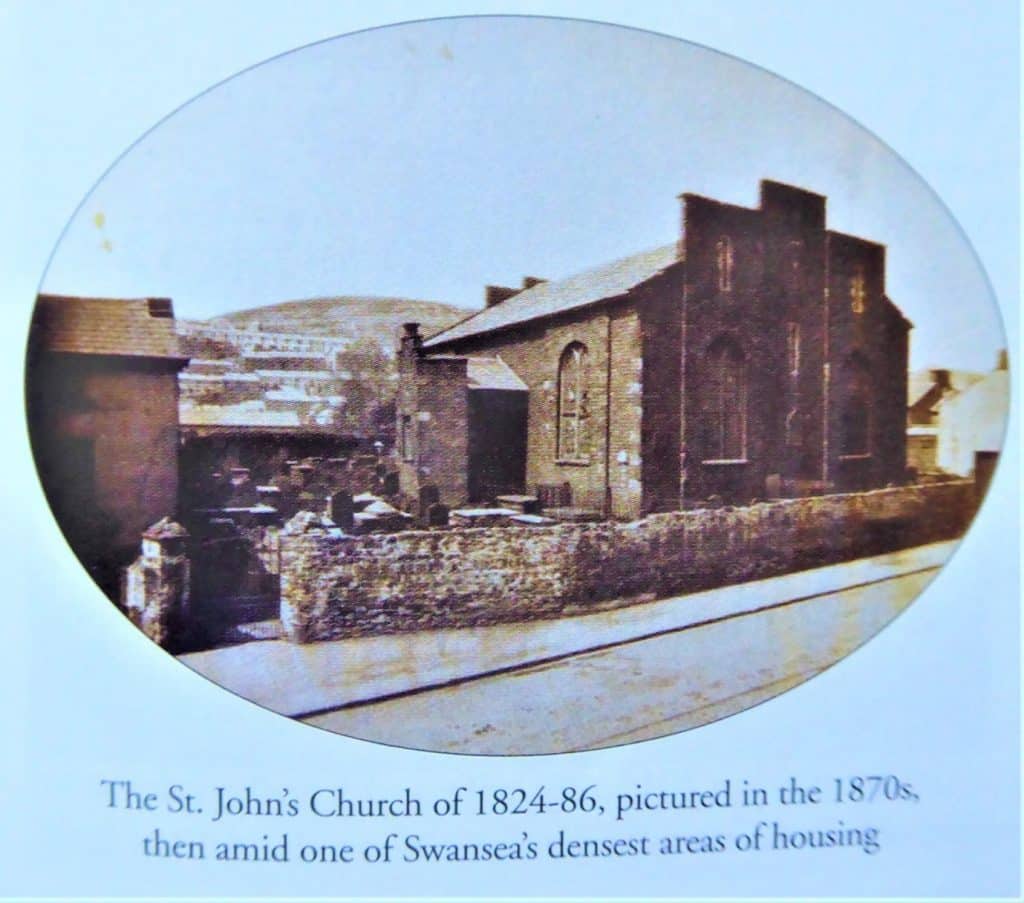

George T. Clark’s 1849 Survey revealed extreme overcrowding and poor sanitation. Swan Street had 38 houses and 28 outdoor privies. In Willow Street, one common privy served eight houses. Back Street hosted 117 houses—64 of which had no toilet facilities at all. Cesspools overflowed. Water was collected from spouts or shallow wells shared by dozens. Poor drainage caused sewage to seep into homes, especially those built downhill from cemeteries.

Samuel Gant’s 1852 Map provided granular insight into every downpipe, cesspool, and privy in the town. It recorded a staggering lack of infrastructure, highlighting how inadequate housing was exacerbated by the absence of piped water and waste systems.

Here is Clark’s description of the streets around St John’s Church copied from his report:

- Swan Street contains 38 houses with 28 privies. In this street are St John’s churchyard and St Mary’s new burial ground; the backs of the houses are damp, and the premises for the most part in a dirty state. Willow Street and its courts include eight houses with two privies. In the court is a common privy in a very filthy condition, the floor rotten and broken, and a large offensive cesspool much complained of. Howell Court contains one privy to four or five houses; it is a long, narrow, close, and ill paved alley. The people pay 1s a week rent and fetch their water from the Dyfatty stream.

- Mariner Street includes 43 houses with 30 privies. Of these, states Mr Davis –

“The floor of one is inundated by the liquid contents of the pit, so that the seat can be reached only by means of large stones. One is shut up, and another very dilapidated, and one too filthy to be entered. The residents buy most of their drinking water at this time of the year, as they can rarely get any at Dyfatty spout without waiting for hours.”

The reputation of this street is very indifferent; the courts and back gardens are dirt. The public way is the exception, and when I saw it was well swept and in good order. Back Street and its courts number 117 houses, of which 64 are without privies.

“The privies” says Mr Davis, “in the courts out of this street (for there is one in most of them) I have reckoned as belonging to the houses in the front of the street. Many families have no place to go to, and there is but an open pit, full in one court. The dwellers get their water at the pump and the spout. There is also a draw well belonging to one or two houses near the upper end. Six new, but filthy, privies opposite Owen Row are included in the account of Mariner Street.”

- The general condition of the Back Street courts is dirty. The people complained much of want of proper privies and a paved surface and said that they would gladly pay 2d a week for such accommodations. Ellery Court is especially close, crowded, and ill paved. The houses are old and dirty; there are but few privies, and the people are very poor. Some of the courts between High Street and the Strand are in bad condition. Thomas Street or Row, and Bethesda Row, and some of the adjacent courts, though broad and airy, are composed of old and ill built houses, without drains and with offensive cesspools. Bethesda Burial Ground is here; it is in a crowded state. The houses hereabouts are pretty well supplied with privies, but the cesspools are complained of as nuisances; still a very moderate expenditure would render this quarter perfectly clean.

- Bethesda Court and an adjacent court are built on the steep hill side and suffer from the sewage and filth from the higher levels. In the former case the cottage wall is also the retaining wall of the burial ground, and the damp oozes through close to the bed-head. Jones’s Court stands on a fine airy platform, and though at present unpaved and dirty might readily be made a pleasant residence. Here I found a small day school filled with merry and healthy looking children. Taylor’s Court is close and filthy; the only privy was a deep open pit. Jockey Street is close and ill paved; the drainage is very imperfect, and the houses are old and badly constructed. Powell Street contains some cesspools much complained of. In the middle of this street are several very respectable houses. This and several of the adjacent courts suffer from the water floods and sewage from High Street.

Census data from this period confirmed severe overcrowding-some two-room homes housed up to 12 people. The residents, primarily industrial labourers and Irish immigrants fleeing famine, were especially vulnerable to outbreaks of cholera and typhoid.

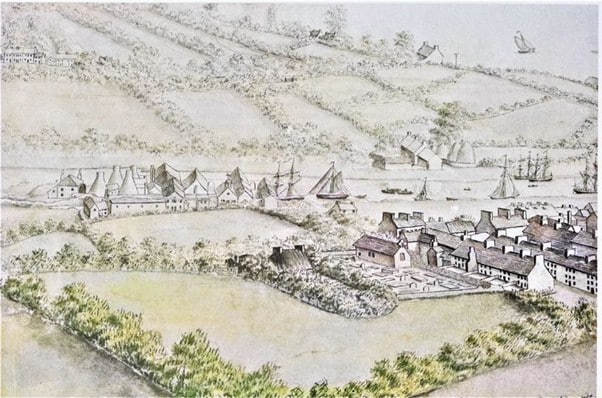

Slum Clearance and the Rise of Alexandra Road

In the 1870s, campaigning began against notorious courts such as Howell’s Court and Regent Court—densely packed alleys synonymous with crime, prostitution, and disease. The passing of the Artisans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings Improvement Act of 1875 empowered Swansea Council to purchase and demolish unfit housing.

However, redevelopment had mixed motives. Instead of rebuilding affordable housing for the poor, the cleared area gave rise to Alexandra Road, lined with prestigious public buildings—the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Dynevor School, and the Central Library. Many poor residents displaced from these slums simply moved to equally overcrowded homes nearby in Greenhill, which were not addressed by the reforms.

Here are some articles, all taken from The Cambrian newspaper, which illustrate the sort of discussions that were being held at the time:

5 Sep. 1873: “cannot some thing be done…”, available at https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3331982/3331987/28/%22Regent%20Court%22:

But the question naturally arises—cannot some thing be done to raise these wretched and miserable creatures from the slough of despond and despair into which they have sunk? Cannot their condition be somewhat ameliorated? Are there no Christian philanthropic agencies which can be applied to rescue some, at least, from their degradation? Or are the denizens of our Regent-court, of our Howells-court, and other notorious localities, so polluted and fallen as to be utterly beyond the pale of reclamation ?—and are they to be given up as ruined—body and soul-lost for ever? Cannot our magistrates, our police, our ministers, our Christian ladies and gentlemen, our religious societies and agents, our angels of mercy, bring some combined efforts to bear upon the misery, sin, and crime, which surround us on every hand?

2 Apr. 1875: “outwardly, at least, our town would be purified”, available at https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3332468/3332473/21/%22Regent%20Court%22:

Now that the Corporation have, or may have, the power to undertake such a work, we recommend to their consideration the advisability of buying up and demolishing all the hovels – the dens of infamy, we have referred to, beginning at the head centre Regent-court. If these filthy alleys and courts were destroyed and wide streets and commodious houses substituted for them, outwardly, at least, our, town would be purified, and the requirements of decency would be met.

14 Mar. 1879: “the scheme will not benefit the artizan population at all”, available at https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3334805/3334810/21/%22Regent%20Court%22

At the time of its initiation, local trade and the public finances were in a highly prosperous condition, and the townsfolk were easily and naturally moved by the sentimental considerations that the poor and teeming population of Swansea ought to be better lodged; that to lodge them better would be to save them from vice and misery; that the scheme would clear from the face of the earth the iniquitous den and purlieus of Regent-court, and substitute a fine roadway and creditable buildings and that the whole could be achieved at a very small total loss to the public exchequer. To-day the condition of things is entirely reversed. Local trade is not brisk, nor public finances plentiful; instead of overcrowding in the borough, there are absolutely upwards of five hundred houses to let; it is now fully recognised that the evils of Regent-street and Back-street cannot be eradicated at one fell swoop but that if the degraded denizens who live on vice and crime be driven from one spot they will settle in another; it has become apparent that the scheme will not benefit the artisan population at all, but will simply open up a wide street, leading only to the residential West End, diverting the business traffic from its proper channel; and that this undesirable alteration will be a loss to the ratepayers in hard cash of at least £50,000. With these striking facts before us, what wonder is it the town has become indifferent to this scheme of Mr. Yeo’s?